Why is Depression Prevalent Among People with Aphasia?

By Laura Phelps

“Aphasia is loss of words, not intellect.”

A man slowly speaks the words with intense focus, as though he’s forcing them out of his mouth. He’s one of eight people featured in a video from Brooks Rehabilitation explaining the condition that makes it difficult for them to communicate.

“Aphasia makes me feel like a half-person,” one woman in the video shares, again with similar difficulty forming the words.

Aphasia is a communication disorder that is typically caused by a brain injury, stroke or brain tumor. About 2.5 million people are living with aphasia in the U.S., according to the National Aphasia Association, but few Americans have ever heard of it.

Aphasia does not affect intellect — only the ability to communicate. There are several types of aphasia that affect people in different ways, whether reading, speaking, writing or understanding spoken language.

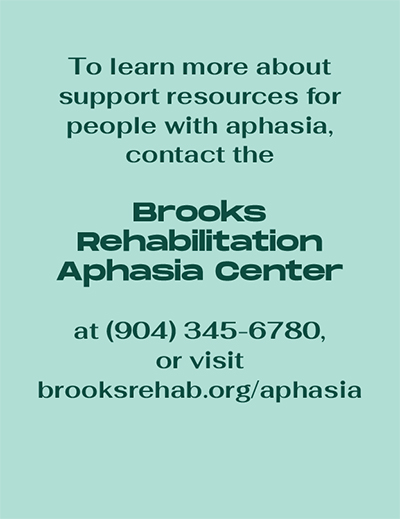

As a speech-language pathologist, Jodi Morgan, CCC-SLP, works directly with people with aphasia to help them find their voice again. She’s not only a professor at Jacksonville University but also the manager and co-founder of the Brooks Rehabilitation Aphasia Center in Jacksonville. Morgan knows all too well the toll aphasia has on people and families.

“If something devastating happens to me, the first thing I want to do is talk to somebody, and they can’t,” Morgan said. “From the moment they wake up in the hospital, they’re excluded from conversations. They’re excluded from making medical decisions. They’re excluded from picking out what they wear, what they eat, their medicine. They don’t even have control of their own life.”

Morgan came up with the idea for a community-based center for people with aphasia and presented it during a Brooks Rehabilitation crowdsourcing initiative. Her proposal won. Within 12 months of opening in 2016, the program was at capacity and now helps around 150 people and their families learn to live successfully with aphasia each year.

While learning to communicate again is transformative for people with aphasia, Morgan knew the center also needed to offer mental health support. Depression among stroke patients is already high — about 35 percent. Among people with aphasia, that number climbs to 70 percent.

“I saw from the day I opened my doors this huge need for counseling,” Morgan said. She was directed to Dr. Natalie Indelicato, associate professor of Clinical Mental Health Counseling at JU and chair of the department. “I literally showed up on her doorstep and said ‘we have a huge need, please help me!’”

Indelicato was moved by Morgan’s tearful plea and jumped in to help. In January of 2020, Indelicato and some of her students started a monthly support group focused on mental health for the members of the center. From the beginning, it was clear the group needed to meet more often.

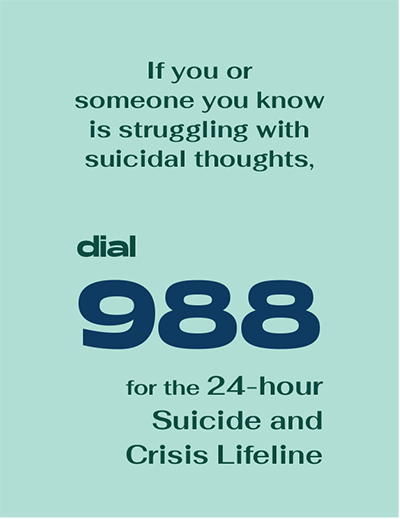

“I remember clearly one of the members talked about her depression and feeling suicidal

in the one of the first groups,” Indelicato said. The woman was a single mom who had a thriving career before

aphasia. “She had never told anybody… because of her challenges with communication,

but also there was really nowhere to communicate that.”

groups,” Indelicato said. The woman was a single mom who had a thriving career before

aphasia. “She had never told anybody… because of her challenges with communication,

but also there was really nowhere to communicate that.”

Within the first month, Indelicato shifted to weekly group meetings. The COVID pandemic forced the meetings into a virtual setting, but the participants adapted quickly, insisting the group continue meeting each week.

“Research says the [rate of depression among people with aphasia] is so high because the challenges to communication affect relationships,” Indelicato said. “It affects careers. It affects financial viability. It basically touches on every aspect of people’s lives. And when there’s such a dramatic shift in functioning, it’s really difficult for people to make sense of that and to incorporate that new identity and way of being into their life.”

Students in JU’s Clinical Mental Health Counseling and Speech-Language Pathology programs helped with the support group as well, either observing or co-facilitating.

“We relied a lot on each other and it became an interprofessional collaboration where students were learning from this unique relationship and we were learning from the members as well,” Indelicato said.

Over time, Morgan and Indelicato noticed the group participants began sharing their feelings more and said the support group helped minimize the stigma of depression and of asking for help. By being vulnerable with one another, participants realized they’re not alone. Some reported having a better outlook on life altogether, including the single mother who shared her struggle with suicidal thoughts in the first meeting.

“She texted me a picture of the sunrise at the beach and wrote, ‘mental health = hope,’” Morgan shared.

After a couple years, the support group meetings moved to twice a week, and Morgan and Indelicato began advocating for a full-time mental health counselor at the center. With grant funding and another crowdsourcing initiative, Morgan hired a full-time counselor in 2023.

Now, more than three years after the first support group meeting, one major takeaway that Morgan and Indelicato have applied in their work is interdisciplinary teaching for their students. They both give guest lectures in each other’s classes to help broaden the skills of students in both disciplines. Indelicato teaches SLP students how to recognize mental health distress and offer support, while Morgan teaches CMHC students strategies for communicating with people who have aphasia, so they feel comfortable offering counseling services to them.

“My dream is to have a lot more mental health counselors embedded in every hospital program in the state of Florida,” Morgan said. “We’re not serving people if we’re only treating their physical impairments and not treating their core.”

Likewise, Indelicato believes mental health professionals must do what they can to

improve access to vital support services, regardless of ability or impairment.

support services, regardless of ability or impairment.

“I tried to put together a referral list for the members, if they had needs that were beyond the support group or for couples counseling or family counseling, and it was very difficult. I spent a lot of time calling [counselors], asking who would feel comfortable being on this referral list for people with aphasia, and nobody even knew what aphasia was,” Indelicato said. “I want every counselor, trainee and private practitioner … to know what aphasia is, have some basic aphasia-friendly counseling skills, and not be afraid to provide services to people with aphasia if they call and request them.”